|

As with most small merchant vessels, the working life of a Sloop was, by definition, neither exciting nor glamorous: they matter-of-factly hauled cargo from place to place, generally unremarked. For a Sloop of Phyllis's age formal paperwork is scant, and what exists is casual and mundane. Writing in 'The River and John Frank,' Nicholas Day records Fred Harness, mate on the Humber Sloop Nero in the nineteen twenties and thirties.

"Shipping records were very basic, a simple diary. There were no statutory obligations. If I was told to load a boat of bricks at Ferriby for Hull, I would go into the office and they would give me a shipping note to hand over at Hull. It just told you what you had in. When I got to the desk I just gave it to the people who bought the bricks. It was a simple chitty. Mr Alf Frank did all the business. It was all cash paymenskills of sailing and handling were learnt on the job, usually from boyhood, although wives also assisted for short periods. A crew of two, Captain and Mate, often father and son, handled the ships with 'purchasemen' bought in as needed. Financially, the ships were run on the 'thirds system. Gross earnings from a trip were deducted roughly 5% to cover dock and canal dues and any towing charges. The net sum was then apportioned one third to the owner, one third to the skipper and one third 'to the ship' - back to the owner to cover mate's and casual labour wages, horse hire insurance's and ship's running and repairs.

By far the largest group of Sloop men and Sloop owners lived in the Waterside area of Barton Upon Humber, effectively a village within the small town, sitting tightly around Barton Haven. At most an area of a square mile, the lanes running westward from Waterside Road still carry the names of local ship owners and builders – Barracloughs, Clapsons and Hewsons. Barton Haven is a late Anglo-Saxon artificial harbour, dug out in c 1000Ad to create a reliable deep-water port for the north of Lindsey. As Hull's fortunes rose as an international port after 1300, so Barton's declined, but it was still an important sub-regional point of connectivity. In the early nineteenth century, a daily mail coach ran from Waterside to Lincoln via Brigg, and from mid-century a three or four times daily paddle steamer ferry to Hull. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Waterside was home to thriving industry. To the east lay two whiting mills, three mills and numerous brick and tile yards on the Humber bank between South Ferriby and Goxhill, most with their own jetty. Local records for 1907 show Waterside Road businesses include coal and coke merchants, brick and tile manufacturers, sailmakers, chemical manure manufacturers, flour and corn millers and animal cake manufacturers, maltings, Clapson's shipyard and dry dock (where the last wooden sloop "Peggy B" was built in 1935), the Norwegian Oil Company and Hall's Barton Ropery, who provided rigging to the Admiralty and, much later, the ropes for Hilary's Everest expedition. During her working life "Phyllis" would have carried products relating to the majority of the Barton industries.

Along with other barges in the general cargo trade, as well as coal "Phyllis" helped to keep the region running during the war years. The first consignment of American lend lease dried eggs arrived in the UK in April 1941: Phyllis was involved in transhipment of lend lease dried eggs and milk from Immingham to Leeds, where it was transferred to shortboats. More critical cargos and duties were to follow. Phyllis was to be caught in the middle of the Hull blitz of 1941.

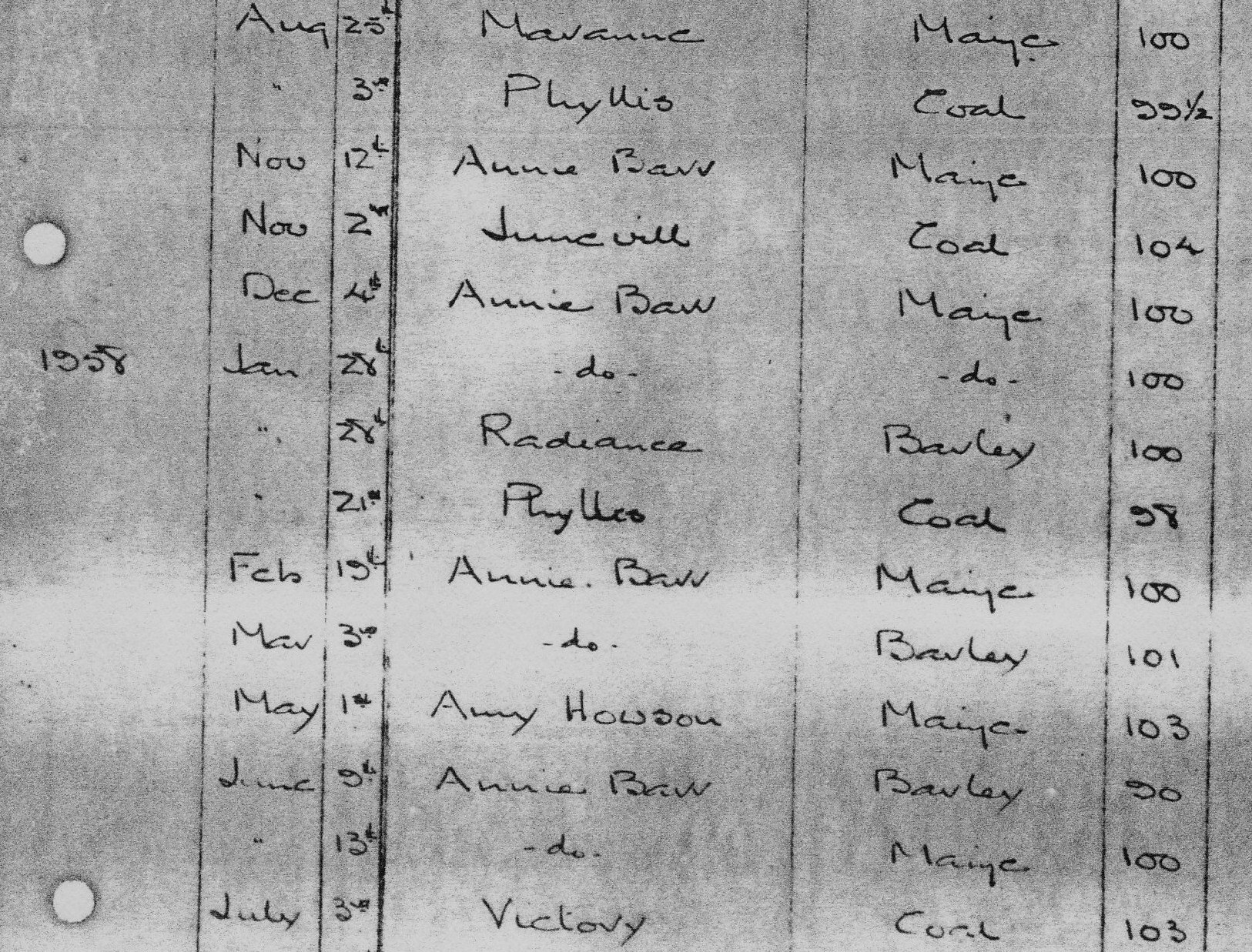

Although "Phyllis" had been throughout W.W.I we do not have any references for the work she undertook. However, we do know that James Barraclough was granted a Freeman of London for the commitment to the continued transportation of coal and commodities during the war. Phyllis would have played a significant part in his achievement of that. Doubtless she was kept busy running coal from the Yorkshire pits to keep the gas works and trawlers going as well as the home fires burning. However for the second war we have accounts from local historians and one of her crew. We also have a copy of captain Harold Harness's diary from 1945 to show exactly what she did during that year along with his wage details and and her towing charges to other companies. For example Harold writes in the front of the diary his wage for 1944, £369.14s 3d of which he paid £43 15s 0d to the P.A.Y.E ("Pay As You Earn" taxation). January 31st to February 4th, loaded bombs. With Fire watch over night and discharging the bombs over the next three days Harold earned £23 15s 10d with overtime and received 150 gallon of fuel. On March 16th 1945 Harold loaded Phyllis with a rare commodity for that time, 60 tons of oranges. Probably the first to reach Hull for a long time. Phyllis then towed "Kate" another of Barraclough's sloops to Grimsby, returning to Alex Dock with Kate still in tow on Wednesday 21st. The maximum cargo carried in 1945 was 146 tons of barly to Selby. After converting to motor barge, "Phyllis" proved to be a popular towing vessel due to her slender lines. Apart from "Kate" already mentioned other barges towed by "Phyllis" during 1945 were; Lillian & May, Lucy, Cressy T, Ivie, Nero, John William, Gertrude, Eva & Lucy, Paul H T and Saira, sometimes two barges at a time were towed. Charges for towing were between 5/- and 13/- (shillings) in new money that's 25p and 65p. During the second war, sloops were commandeered to help with the war effort, some like "Vi" and "Gravel" were deployed as barrage balloon vessels by 17th Balloon Centre RAF Sutton on Hull. I don't have any info on "Gravel" but "Vi" was built by Warrens in 1925, yard number 205. She was sank in West Walkier Dykes in 1935, raised and put back into service.The North East Diaries 1939-45 (NED) compiled by Roy Ripley and Brian Pears give contemporaneous accounts of the scale of events drawn from local fire and civil defence logs amongst other reports across the City. During the day of the 7th May 1941, the barge "Ril IIda" ( Spillers lighter) had been sunk in Hull, and, just off the Humber, the auxiliary patrol trawler "Suserian" bombed. That night, the attacks began in earnest.

Harry Turner's account tells us:

- "Sure enough the next night, which was clear and moonlit, our station at Spurn Point called us with 'Pip up — hostile target on bearing 95 degrees'. We found a lone target, possibly a reconnaissance plane to draw our guns whilst the rest of the pack sneaked in. The guns deliberately did not fire, but an hour later all stations were reporting targets and the guns engaged but it was really difficult as the heights were very varied. The sight of Hull being bombed was enough to make you weep; it was worse than the night before. The air was filled with the noise of aircraft and our shells whistling up whilst the bombs whistled down. The Luftwaffe had the advantage that even if their bombs missed the docks and factories they would hit civilians in their houses nearby, and hundreds of Hull people were killed before the enemy departed at around 5am leaving the city centre devastated. If the Germans had come a third night I think there would have been nothing left of Hull. The air raid wardens, firemen, army and everyone were worn out but the docks were still functioning and Hull was down but not out".

-

- David Carruthers remembers standing on the Humber foreshore at New Holland, about two miles away. He says, "We just watched Hull burn. You could feel the heat from here."

- Phyllis's captain before WW2 was Captain Tom Kerridge then Captain Harry Horsefall and later Captain Harold Harness who had served as mate with Captain Horsefall, (Harold's son and mate aboard "Phyllis" in later years had the same name) who had been with her since May 3rd 1943 and remained with her until the late 'forties. David Carruthers joined him aboard "Phyllis" as a fifteen year old mate in early 1944.

-

- Almost the whole of the riverside was razed by fire, Riverside Quay and Alexandra docks were damaged. Ruins along the banks of the river Hull (a small tributary of the Humber) included flour mills and stores bearing such names as Ranks - Spillers - Gilboys - Rishworth - Ingleby and Lofthouse. King George Dock itself simply had to be protected at all costs. Working constantly under what rapidly became a firestorm, Phyllis's role was to identify and tow any fired vessels out of the dock many carrying highly flammable or combustible cargo, leaving them to chance burning, sinking or going out against an adjacent jetty just known as "Number 80". Oldridges's 1894 ship Lily was one of those destroyed.

- As events unfolded, in the course of his duties with "Phyllis" to help tow burning and damaged barges from the dock captain Horsefall and crew were periodically required to swiftly remove a variety of incendiary devices falling on Phyllis's own wooden hatch covers, largely by the simple expedient of kicking them off. The British Transport Police Roll of Honour records PCs John Woods and George Barker of the LNER Police as being found dead at the entrance to King George Dock at the end of the 8 May raid. John Woods was fifty two, George Barker was sixty five and due to retire.

- Wartime barge crew were formally classed as merchant seamen, their roughly average weekly commercial wage of twenty one shillings supplemented by an entitlement to double rations. Barges standing fire watch received a Ministry of War Transport allowance of eight pounds a week, which probably generously reflected the demurrage payment system, but also acknowledged the significance of the vessels' civil defence role.

- The end to Phyllis's Second World War career finds her more quietly in 1944, with a new electric deck winch fitted, powered by a 3.5 horsepower petrol paraffin Lister engine, and an excited David Carruthers in his first week at work taking chalk from South Ferriby cliffs to Spurn Point, and seaward with gravel to Withernsea where Barraclough's had a contract with Westminster Dredging. On that trip, under the doubtless close scrutiny of captain Harold Harness, German and Italian prisoners of war offloaded her cargo.

- Later still, in the extreme winter of 1947, David Carruthers recalls "Phyllis" spent eight weeks stuck on the icebound Aire and Calder canal on a run with chalk from South Ferriby quarry to Thwaite's mill at Leeds. The ship itself was only saved from being frozen in by hot engine cooling water discharged from the passing Tom Puddings on their daily run from Leeds to Wakefield. Cement to Wakefield was a cargo he particularly disliked: bags were hauled out of the hold two at a time by horses, and it was only possible to get cement dust out of his hair by lathering it in margarine. Later promoted to Captain of the larger Barraclough's motor barges, for example "A Triumph", "Marranne" and "Juneville", David Carruthers stayed with the company until he came off the waterways in 1965.

- In a curious footnote, Phyllis's working life became rather more varied in the early part of her retirement from service. Sold on in 1974 by Barraclough's with her working companion John William when the firm closed, Phyllis made a voyage up to Scotland and at one time had been intended for use as a supply lighter to the oil rigs. Her hulls' complete unsuitability for that type of work must have quickly become apparent. But she did join the hunt for "Nessie". after being reunited once more by pure chance with her old working partner John William. But that's a part of someone else's story.

|