|

|

|

|

|

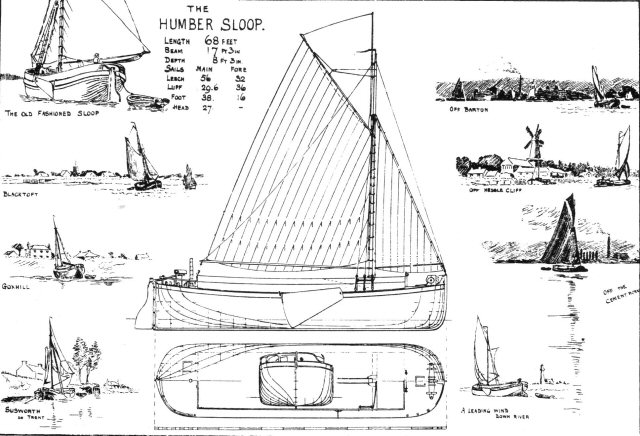

The Humber sloop was very much influenced by the Dutch and honed into a versatile workhorse by the men that sailed them over a period of 250 years. Using a single mast employing a loose footed gaff rigged main sail, self tacking foresail and a range of head and top sails the sloops traded within and between the Humber and other east coast regions from the early 18th century and are depicted on maps showing the River Aire at Leeds in 1725. Some being able to carry over 170 tons the early wooden Humber sloops were between 57ft and 68ft Loa with a beam between 16ft and 18ft, the later steel hulled sloops could be as much as 72ft Loa, all were significant in the evolution of national and international trade on the Humber being a valuable tool to the merchants who traded goods to home and foreign ports. They were the region's equivalent to the modern day coaster, providing a means of transporting large and mixed cargoes between ports on the Humber and along the east c oast where shallow drafted flat bottomed vessels were essential to navigate small creeks, havens and inlets. Some would trade to the near continent with a crew of four to stand a two man alternate watch while at sea. Strongly built of oak initially using clinker construction the sloops were later built using a method employing both carvel and clinker construction, during the second half of the 19th century the construction would turn to fully carvel built vessels and by 1880 iron was beginning to be used in local yards. By the start of WW1 steel was being used throughout the shipbuilding industry but wooden craft were still also being built in yards like Dunstons at Thorne and Clapson & Son at Barton. oast where shallow drafted flat bottomed vessels were essential to navigate small creeks, havens and inlets. Some would trade to the near continent with a crew of four to stand a two man alternate watch while at sea. Strongly built of oak initially using clinker construction the sloops were later built using a method employing both carvel and clinker construction, during the second half of the 19th century the construction would turn to fully carvel built vessels and by 1880 iron was beginning to be used in local yards. By the start of WW1 steel was being used throughout the shipbuilding industry but wooden craft were still also being built in yards like Dunstons at Thorne and Clapson & Son at Barton.

The sloops of the Humber could be divided into two basic groups; those that traded regularly to coastal ports and havens, and those that traded inland within the confines of the Humber and its tributaries, locally known as "river sloops". From the 19th century those in the regular coasting trade were given a Certificate of British Registry and a unique signal flag sequence that was flown while at sea for identification purposes. Rodney Clapsons book; Barton and the River Humber, ISBN 0 900959 20 7 highlights the system and gives details of many of the local sea going sloops that where given code flags.

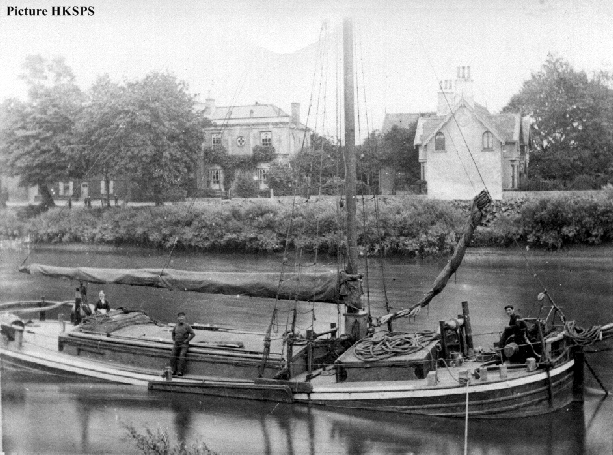

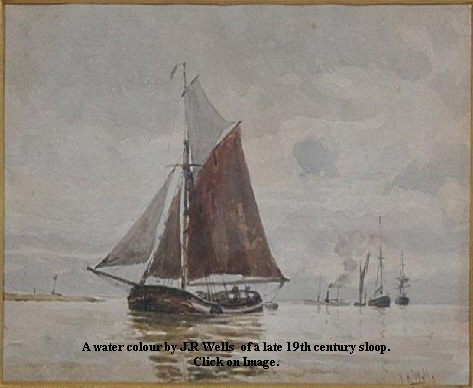

The early coasting sloops were equipped with two separate holds and had little need to lower their mast in the course of their work. They were rigged with either topmast or a pole mast (full length single mast) which could be rigged with a variety of topsails, the bow was short stemmed (the top of the stem being level with the deck) to be fitted with standing bowsprit and jib. Some flew a second jib or jib top sail. Depending on the top sail arrangement they may also have been rigged with rattlings (rat lines) on the shrouds to enable the crew to work aloft, all making them more efficient at sea. From early 18th century paintings we can tell that very early wooden  sloops carried a huge flat peaked main sail with the boom extended over the after deck, the popular topsail arrangement was a four sided sail hoisted on a short yard rather like a dipping lug or a triangular sail hooped to the topmast and worked from aloft using the rattlings. These big seagoing sloops must have been a colourful sight on the Humber with all sails set, from remarks in his book (Humber Keels and Keelmen. ISBN 0 86138 059 2) keelman Captain Fred Schofield tells us that traditionally the seagoing sloops had tanned main and fore sails but the top and head sails were white, some however had all white sails (Ref:- Reuben Chappell, Elizabeth Ann 1860) others are depicted with all tan sails, much would depend on cost and availability as sails from de-rigged or decommissioned vessels were often used on others. They were also known to carry (depending on the captain) a square sail and yard that would be used at sea in light airs or on the inland waterways like the River Hull that they could navigate under sail making them easy to mistake for a keel on old photos (Click on picture above). The white sails were often referred to as "Summer Sails" and would be stowed in the fore cabin in winter which is a reason for them not to be preserved by the tanning process, they would have been very smelly. The winding gear for hoisting the sails consisted of a pair of triple rollers being located each side of the mast athwart ship (Across the beam) in the "sparring" a section of deck between the two holds, the mast was stepped in a lutchet mounted on deck. Being more of a fixture than the inland sloops with no fore stay tackle permanently rigged plus the fact that the mast was stepped between the aft and forward hold meant that it could not readily be lowered. Above right, is a picture that may be of Humber sloops employed in the sand and gravel trade. Speed to and from the sand and gravel sites at Goole, (Sand Hall Reach) Paull and particularly Spurn Point was paramount in catching the right tidal conditions for beaching in the correct location giving time enough to load the sloop before the flood (Phil Mathison, The Spurn Gravel Trade. ISBN 978 0 9546937 6 3). sloops carried a huge flat peaked main sail with the boom extended over the after deck, the popular topsail arrangement was a four sided sail hoisted on a short yard rather like a dipping lug or a triangular sail hooped to the topmast and worked from aloft using the rattlings. These big seagoing sloops must have been a colourful sight on the Humber with all sails set, from remarks in his book (Humber Keels and Keelmen. ISBN 0 86138 059 2) keelman Captain Fred Schofield tells us that traditionally the seagoing sloops had tanned main and fore sails but the top and head sails were white, some however had all white sails (Ref:- Reuben Chappell, Elizabeth Ann 1860) others are depicted with all tan sails, much would depend on cost and availability as sails from de-rigged or decommissioned vessels were often used on others. They were also known to carry (depending on the captain) a square sail and yard that would be used at sea in light airs or on the inland waterways like the River Hull that they could navigate under sail making them easy to mistake for a keel on old photos (Click on picture above). The white sails were often referred to as "Summer Sails" and would be stowed in the fore cabin in winter which is a reason for them not to be preserved by the tanning process, they would have been very smelly. The winding gear for hoisting the sails consisted of a pair of triple rollers being located each side of the mast athwart ship (Across the beam) in the "sparring" a section of deck between the two holds, the mast was stepped in a lutchet mounted on deck. Being more of a fixture than the inland sloops with no fore stay tackle permanently rigged plus the fact that the mast was stepped between the aft and forward hold meant that it could not readily be lowered. Above right, is a picture that may be of Humber sloops employed in the sand and gravel trade. Speed to and from the sand and gravel sites at Goole, (Sand Hall Reach) Paull and particularly Spurn Point was paramount in catching the right tidal conditions for beaching in the correct location giving time enough to load the sloop before the flood (Phil Mathison, The Spurn Gravel Trade. ISBN 978 0 9546937 6 3).

|

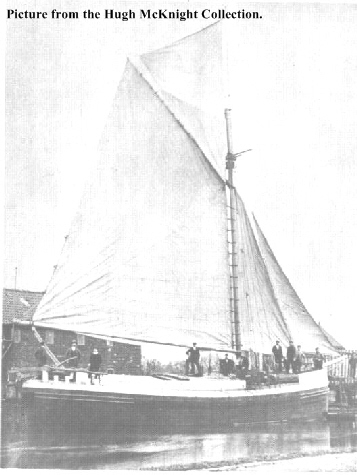

A typical late 1800's Humber sloop, "Hydro" at anchor in the Trent. The hold arrangement can clearly be seen. (Slabline, issue 68. 2008)

Those that didn't trade seaward, referred to as river sloops, had the option of a yarded topsail or a well-peaked main sail with foresail and were built with a single full-length hold. With much less rigging they were easier to manoeuvre in the locks and docks although the market sloops that seldom used any locks would carry a bowsprit and jib. Double rollers for hoisting the sails were set against the coamings (the sides of the hold), and because they were mounted sideways on they were known at "crab" rollers. A removable mast-way provided in the hatches allowed the mast to be lowered aft between a set of short hatches. The mast stepped in its lutchet some 3ft below the hatches was lowered by means of the permanently rigged fore stay blocks controlled by a fore roller attached to the front of the hold area above deck that was known as the forward head ledge. The sail would first be unlaced from the mast hoops, and then the gaff and boom complete with the sail would be removed and stowed on the hatches. Both coasting and inland sloops had heavy oak and pitch pine leeboards operated from the aft deck by a vertical roller set into the fore end of the after rail. The seagoing sloops would probably have had a more slender leeboard than the inland working sloops where greater effect from them was desired in the strong tides and shallow water of the Humber . At sea with a light sloop the leeboards may not even have been used in some sea conditions as the ships were better balanced with their more efficient sail configuration, a loaded sloop wouldn't have normally used them.

Sloop dimensions where usually larger than that of the keels, and the sloops were not particularly suited to working far inland from the Humber, Trent or Ouse. One disadvantage of the sloop for inland work was that it could take even a practised crew 40 minutes or more to lower the mast whereas a keel crew could have the mast down in less than ten. The restrictions on width and air draught along parts of the canal system meant that the sloops would need to un-ship their leeboards and mast to leave along with their cog boat at strategic points like Stainforth on the Keadby and Stainforth navigation to be able to navigate the rest of the waterway. The parts of the system that could be navigated without removing the leeboards however may still involve lowering the mast at some point. Time spent lowering the rig could make the difference in engaging a horse marine or bow yanking your own barge up the canal and it was impossible for a sloop to shoot a bridge. Both being reasons why keels were preferred in the inland trade to sloops.

|

The staithe at Stainforth showing the crane used to unship sailing gear, masts and spars with a collection of leeboards can be seen to the left of the crane.

However many did trade inland and this brought about the same restrictions of hull size as the keel that depended on which waterway they worked. There were ten differently named and historically recognised variations of types of keel and in turn variations of the Humber sloop used for trading inland from the Humber, none being greater than 15ft 8" beam. These were; Sheffield 61ft 6" by 15ft 6", Barnsley 70ft by 14ft 4", West Country 57ft 6" by 14ft 2", Manvers, Wath, Dearne & Dove 57ft 6" by 14ft 8", Driffield 61ft by 14ft 6", Louth 72ft by 15ft, Trent 74ft by 14ft 4", Lincoln 74ft by 14ft 4", Horncastle 54ft by 14ft 4", and Market Weighton 66ft by 14ft 6". Note; The West Country size of vessel is relating to ships on the Calder and Hebble Navigation, not from Cornwall or Devon.

Of course not all these waterways had sloops working on them, some were the domain of the keel and remained so until the motor took over from sail. The above dimensions are those that are recounted in history and several well read publications, however, the dimensions themselves must have altered with the evolvement of the individual waterway. A sketch in the HYC Yearbook from 1901 by George Holmes of a Sheffield size keel shows the vessel being 60ft 3" by 15ft 3". The width and length of the locks built by the local Waterway Authority and the depth of the water determined the size of vessel that could be used along the navigation forcing the cargoes to be hauled by the Authorities own craft, ensuring both navigation fee's and cargo handling fee's were collected from the owners of larger craft. Of course the narrower and shallower the canal, the cheaper it was to build. Also, the industry along the waterway may not have been economical enough to employ large vessels so why build a large waterway. The Sheffield size barge was born in 1814 with the opening of a section of canal that brought the waterway into the city centre, joining the River Don at Tinsley. One or two captains of these smaller vessels would during the summer take on cargo's for the Wash ports like Boston and Hunstanton returning with shingle for Grimsby off the beach at Snettisham. Dick Cook of Owston Ferry was one of these captains who along with his son and grandson as crew traded to the Wash with their sloop "Sarah" built at Gainsborough in 1889. (Fred Schofield, Humber Keels and Keelmen. ISBN 0 86138 059 2 ). The passage into and out of the Wash was helped by the predictable tide run that flowed past the Humber and down into the Wash. The Sheffield size was the a usual variation of the Humber sloop and is the best known and the closest comparison to vessels like "Phyllis" but of course there were many built of a size that suited their owners requirement or pocket that may well have been different to these recognised dimensions. One of the smallest sloops seen on record was "Two Brothers" at just 37ft 5" Loa by 14ft 2" beam, built at Gainsborough in 1803. (Rodney Clapson; Barton and the River Humber, ISBN 0 900959 20 7)The bluff bow and stern of the Sheffield sloops fitted snugly into the locks of the waterways they traded on allowing them to maximise the cargo space and gave excellent buoyancy in the relatively flat water of the Ouse or Trent. They could also be loaded to maximum draught in the canals carrying as much as 117 tons, it was the theory that the buoyancy in the fore and aft end of the ship provided by the cabin space was enough to keep it afloat if the hold flooded that the captain relied on to carry as much as possible. When loaded on the Humber in rough weather water would crash up over the horse plate flooding the fore deck and down the side of the ship, if she started to nod in a series of big swells the bow would dip under water bringing her to a stand-still and waves would roll over the hatches down the ship and could wash the helmsman overboard from the after deck. I remember watching motor barges as a lad heading up river past Barton with waves rolling down the hatches and breaking over the wheel house when the bow dipped in. The bows on the Humber sloops were more rounded offering less resistance and the hulls had a more pronounced shear; this kept her head up when loaded, although water could often be on the side decks while sailing, the rounder bow gave better sea keeping qualities. The seagoing sloops were bound by insurance regulations regarding freeboard (the height of the deck above water) and always returned in ballast if no cargo was available helping to stabilise the ship. With their flat bottoms and round bilge the sloops were well known for their ability to roll violently in a beam sea and is something we have had first hand experience of with "Phyllis".

I just want to touch on the term "Billy boy sloop". It is heard from time to time and has had, in my view, incorrect definitions in a collection of publications. The vessels were origially wooden coasting sloops from the Humber or Yorkshire region and differed from the areas "river" sloops.

River sloops mainly differed from Billy boy, or coasting sloops in their lack of bulwarks and a differnt halyard roller arangement and simple sail plan easily handled in the relitive confines of the Humber and associated waterways. The coasting sloops had gaff mainsail and all round bulwarks with leeboards, a bow sprit flying a jib or two, and a topsail, the hold was sectioned into two with a sparring deck between where the mast was stepped with heavy tripple halyard rollers port and starboard. So, "Billy boy" was the colloquial term for a small coasting sailing vessel that hailed from Yorkshire or the Humber region, although it seems vessels from the north east coasting trade in genaral could be reported on as such.

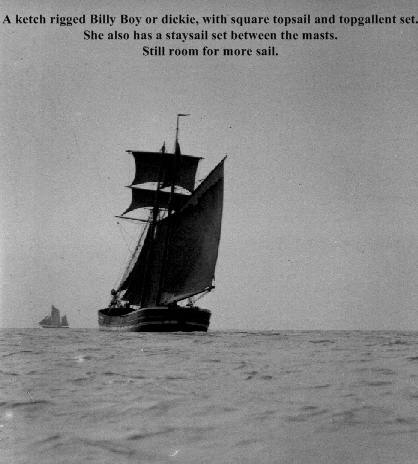

The identity of the Yorkshire Billy boy changed in tune with trade and demand for larger cargo's, the two masted Ketch rigged vessels took over much of the sloops trade and flew as much sail as possible using not only gaff but square yarded sails and a range of head-sails and topsails, some had square topsails and topgallants. These Billy boys were bluff but sometimes clipper bowed depending on their trade with a full round stern, high bulwarks and a prominent sheer. Most were large vessels of about but not limited to 68ft Loa and over 17ft in the beam but some were small enough to work inland from the Humber and were also flat bottomed for the same reason as the sloops; to work in havens and off the beaches when required and not all carried leeboards. It is with the ketch, built, owned or associated with Yorkshire that the term "Billy boy" has become synonymous. It should be noted that the term "Billy boy" is not particular type of vessel usually found in official registers but vessels known locally as such are more often listed as a ketch, but this colloquial term could also be applied to a schooner or sloop rigged vessel in the coasting trade.

With a hull shape more suited to sailing another ketch rigged vessel was found on the Humber as in the picture above left, these vessels were locally known as a "dickie" as indicated by Fred Schofield in his book "Humber Keels and Keelmen". I just want to touch on the term "Billy boy sloop". It is heard from time to time and has had, in my view, incorrect definitions in a collection of publications. The vessels were origially wooden coasting sloops from the Humber or Yorkshire region and differed from the areas "river" sloops.

River sloops mainly differed from Billy boy, or coasting sloops in their lack of bulwarks and a differnt halyard roller arangement and simple sail plan easily handled in the relitive confines of the Humber and associated waterways. The coasting sloops had gaff mainsail and all round bulwarks with leeboards, a bow sprit flying a jib or two, and a topsail, the hold was sectioned into two with a sparring deck between where the mast was stepped with heavy tripple halyard rollers port and starboard. So, "Billy boy" was the colloquial term for a small coasting sailing vessel that hailed from Yorkshire or the Humber region, although it seems vessels from the north east coasting trade in genaral could be reported on as such.

The identity of the Yorkshire Billy boy changed in tune with trade and demand for larger cargo's, the two masted Ketch rigged vessels took over much of the sloops trade and flew as much sail as possible using not only gaff but square yarded sails and a range of head-sails and topsails, some had square topsails and topgallants. These Billy boys were bluff but sometimes clipper bowed depending on their trade with a full round stern, high bulwarks and a prominent sheer. Most were large vessels of about but not limited to 68ft Loa and over 17ft in the beam but some were small enough to work inland from the Humber and were also flat bottomed for the same reason as the sloops; to work in havens and off the beaches when required and not all carried leeboards. It is with the ketch, built, owned or associated with Yorkshire that the term "Billy boy" has become synonymous. It should be noted that the term "Billy boy" is not particular type of vessel usually found in official registers but vessels known locally as such are more often listed as a ketch, but this colloquial term could also be applied to a schooner or sloop rigged vessel in the coasting trade.

With a hull shape more suited to sailing another ketch rigged vessel was found on the Humber as in the picture above left, these vessels were locally known as a "dickie" as indicated by Fred Schofield in his book "Humber Keels and Keelmen".

In 1840 the Humber sloops were busy with one of the most challenging haulage contracts that they could wish to undertake. The stone to rebuild the Houses of Parliament was to be cut from North Anston Quarry and transported along the Chesterfield canal by " Cuckoo" boat to be transhipped onto Humber sloops at West Stockwith for the trip down to London and up the Thames. Offloaded near to the site of the new building each sloop chartered would carrying 110 ton of stone and made the trip to London and back each week until completion. The book "Yorkshire Stone to London" (ISBN 978-0-9552609-2-6) by Christine Richardson tells the whole story.

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Phyllis" pictured above off Barton in one of the Barton Sloop Regatta's. The year is unknown but judging by the condition of her sails and hull it must have been when she was fairly new, certainly pre 1914. The Barton Waterman's Regatta had been established in 1887 and was halted by the outbreak of war in 1914. The regatta's were resurrected in 1922. The last Barton Regatta was held in 1929, won by "Saxby" her captain was Charlie East. We were told by the late sloop man Charlie Atkinson that "Saxby" only won the race because they ran over the cog boat of "Zenitha" owned by Fosters of Barrow Haven and with Arthur Foster as captain, she then had to tow a sunken boat allowing "Saxby" to take the lead. (This story is also told by Captains John Frank and Clarence Foster so is well documented) Sheffield size "Zenitha" was later sold to Eccles to carry chalk for bank repairs. Charlie also told us that "Phyllis" won the 1926 regatta but unfortunately this time he was mistaken, we now have evidence that proves otherwise, research is always ongoing around undocumented information. However, "Phyllis" seems only to have taken part in the regattas pre WW1, and in those days photographs were only taken of meaningful events and this could be a picture of a winning vessel.... Just maybe! |

|

|

|

|

|

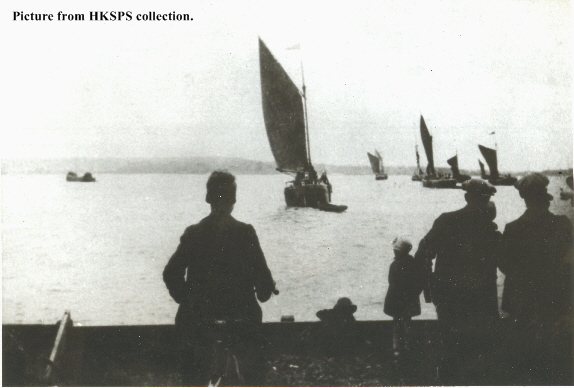

Right. The start of the last Barton Regatta off Barton Point in 1929. The Barton Waterman's Regatta had begun in 1887 and was holted during the 1914-18 war. It was revived by the Barton branch of the British Legion in 1922. Any wooden sloop taking part would be given a 30 minute head start against the steel sloops and were in later years judged as a different category. The prizes were of course a cup and a medal for the captain, also cash and other prizes were given by local businesses. The most prestigious item to win was the "Golden Cockerel" which was awarded to the winning sloop, to be flown from its mast head for the following year. There were other classes of race during the regatta weekend but the sloop race was the main event and became known as the "Cock of the Humber". A race bearing that title is still run every year on the Humber by the Hull Sailing Club. It would be interesting to enter "Amy Howson", "Phyllis" and "Spider T" one year. With the application of PYS rules of course. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left. This is the actual "Copper Cockerel" that was last awarded to the sloop "Saxby" in the very last Barton Waterman's Regatta which took place on August 3rd 1929. The cockerel is owned by the Humber Keel and Sloop Preservation Society and is presently kept at the Barton Museum in Baysgarth Park. The society also has the pennant flown by the committee boat from that last race in which thirteen sloops took part having to contend with a gale on the return leg. The listed finishing sloops were - Iron vessels; 1. Saxby, 2. Zenitha, 3. Alva S, 4. Swinefleet, 5. Salvager, 6. The Humber (Humber T.) Wooden vessels; 1. Faxfleet, 2. Burgate, 3. Alice, 4. Lilian and May, 5. Thistle, 6. Spider T. Why Spider T is listed with the wooden sloops is unclear, she is definitely a steel vessel. (Steel built ships were still referred to as "Iron") No doubt a journalistic error. Click on www.keelsandsloops.org.uk to visit the HKSPS web site. |

|

|

|

Although iron ships were being built in Hull from 1831 by James Livingston, progression in the use of iron and steel to build barges was much slower. Richard Dunston's yard at Thorne didn't build steel barges until 1917 and their last wooden keel in 1922, some yards like Brown and Clapsons of Barton on the other hand only ever built wooden barges, the last being the sloop "Peggy B" in 1935. The use of firstly iron and soon after steel in the construction of barges in the Humber region didn't commence until around 1880 when the coasting trade for the sloops was fading and merchants wanted cheaper ships. Iron vessels started to be produced of similar dimension to the wooden sloops. Using perhaps Dutch or Thames barge influence, a topping-up or steeving bowsprit was used either set under the anchor windlass housed in a slot next to the stem in the horse plate, or set over the horse plate and pivoted from a stanchion set behind the anchor windlass This gave a degree of flexibility in the cargos that were undertaken and allowed navigation of at least some of the inland locks and rivers, something that was required in the battle with the progress of the rail network. A hinged bracket arrangement bolted to the stem was sometimes used on steel built Sheffield sloops but being a fairly light arrangement was probably used only in relatively calm conditions on the river. Sheffield sloops were not involved in the regular coasting trade. With the downturn in coasting trade at this time not many of the steel sloops would have worked coastal. However one that did was "Brilliant Star" built at Beverley in 1893 for Sowerby &Co Ltd of Grimsby official number 118822 at 77 grt and 75 ft Loa. She was under the command of Captain Nettleton, she had all the attributes that the wooden sloops had beforehand including two holds and a sparring deck, she traded to Wells, Snettisham and Kings Lyne from Hull with animal feed from the cake mills along the River Hull as well as other produce . She became part of the Eastwood families fleet in 1905 and was captained by George Hardy of Hull. She was fitted with an engine in 1933. progression in the use of iron and steel to build barges was much slower. Richard Dunston's yard at Thorne didn't build steel barges until 1917 and their last wooden keel in 1922, some yards like Brown and Clapsons of Barton on the other hand only ever built wooden barges, the last being the sloop "Peggy B" in 1935. The use of firstly iron and soon after steel in the construction of barges in the Humber region didn't commence until around 1880 when the coasting trade for the sloops was fading and merchants wanted cheaper ships. Iron vessels started to be produced of similar dimension to the wooden sloops. Using perhaps Dutch or Thames barge influence, a topping-up or steeving bowsprit was used either set under the anchor windlass housed in a slot next to the stem in the horse plate, or set over the horse plate and pivoted from a stanchion set behind the anchor windlass This gave a degree of flexibility in the cargos that were undertaken and allowed navigation of at least some of the inland locks and rivers, something that was required in the battle with the progress of the rail network. A hinged bracket arrangement bolted to the stem was sometimes used on steel built Sheffield sloops but being a fairly light arrangement was probably used only in relatively calm conditions on the river. Sheffield sloops were not involved in the regular coasting trade. With the downturn in coasting trade at this time not many of the steel sloops would have worked coastal. However one that did was "Brilliant Star" built at Beverley in 1893 for Sowerby &Co Ltd of Grimsby official number 118822 at 77 grt and 75 ft Loa. She was under the command of Captain Nettleton, she had all the attributes that the wooden sloops had beforehand including two holds and a sparring deck, she traded to Wells, Snettisham and Kings Lyne from Hull with animal feed from the cake mills along the River Hull as well as other produce . She became part of the Eastwood families fleet in 1905 and was captained by George Hardy of Hull. She was fitted with an engine in 1933. At left and below is the overgrown wreck of "Brilliant Star". She was painted in a similar style to local marine artist Reuben Chappell in full sail in her hay day as a proud Humber sloop trading with east coast ports but now lies rotting and forgotten amidst the prosperity her predecessors brought to the 21st century Wakefield town centre. Although "Brilliant Star" has been sunk for over 5 years she still has her trade mark feathering plates that outlined the purposeful bow and the twin head ledges that depicts her sparring deck can still be seen. No longer are the lines of her hull visible to show off the riveted plates of her hull or to give outline to her Humber sloop profile. At left and below is the overgrown wreck of "Brilliant Star". She was painted in a similar style to local marine artist Reuben Chappell in full sail in her hay day as a proud Humber sloop trading with east coast ports but now lies rotting and forgotten amidst the prosperity her predecessors brought to the 21st century Wakefield town centre. Although "Brilliant Star" has been sunk for over 5 years she still has her trade mark feathering plates that outlined the purposeful bow and the twin head ledges that depicts her sparring deck can still be seen. No longer are the lines of her hull visible to show off the riveted plates of her hull or to give outline to her Humber sloop profile.  These pictures of "Brilliant Star" taken by us on 6th April 2012 demonstrate the fate of most of the Humbers sailing barges. It is very easy to think that lying here could just as easily been any one of the handful of restored keels and sloops that sail again today. Unfortunately here lie's a truly unique vessel that provides us with that step in maritime history when construction of the Humber sloop progressed from wood to steel and also represents the last days of trade from the Humber under sail. It is hoped that more research on "Brilliant Star" will take place. These pictures of "Brilliant Star" taken by us on 6th April 2012 demonstrate the fate of most of the Humbers sailing barges. It is very easy to think that lying here could just as easily been any one of the handful of restored keels and sloops that sail again today. Unfortunately here lie's a truly unique vessel that provides us with that step in maritime history when construction of the Humber sloop progressed from wood to steel and also represents the last days of trade from the Humber under sail. It is hoped that more research on "Brilliant Star" will take place.  The Humber sloop "Hydro" Off No 106737 and built in 1897 in a staged photograph with her at anchor in full sail on the Ouse. She ran Phosphate between Howden Dyke and Boston. (Slabline, issue 68. 2008)

The Humber sloop "Hydro" Off No 106737 and built in 1897 in a staged photograph with her at anchor in full sail on the Ouse. She ran Phosphate between Howden Dyke and Boston. (Slabline, issue 68. 2008)

With evidence from the Mariners Mirror in a 1950's article by John Frank, brickyard owner and captain of the sloop Nero, we can determine that the cutter-rigged sloops with their contrasting white and tan sails had begun to disappear around 1910 having been in decline since around 1870. By then the sea going trade for the sloops had gone largely to the faster and more able ketch rigged Billy boys, steamers and schooners. Some evidence however does exist to show that the bowsprit and jib had been kept on some river sloops up until 1921, some minor coastal trade by Humber sloop into the ports of the Wash may have been present but were infrequent. With rail connections spreading fast and the rail companies now controlling the canals and ferries there became no requirement to use the creeks and havens of the east coast to deliver or collect produce and materials. A large number of the sailing barges, sloop or keel built after this time to work on the Humber in general cargo were largely of Sheffield size and motor barges were starting to appear in greater numbers, many also Sheffield size. Perhaps the reason for the popularity of the Sheffield size of vessel was in the relative cheapness of building them or their ability to carry a significant amount of cargo in the sometimes demanding environment of the Humber and still be able to trade well inland. Dave Robinson from the HKSPS once described the Sheffield size sloops and keels as "the Transit vans of their day", reflecting their wide and varied use. It is a testimony to their versatility that many of these size of Humber sailing barge, predominantly the keel survive today, not only the length and breadth of England but they have been seen in France, Holland and Germany. The examples that I am aware of are; Sheffield sloops; "Amy Howson" (although originally built as a keel) and "Spider T", the little market sloop "Kama" went to Germany. Sheffield keels; "Comrade", "Daybreak" (Daybreak was the last keel to be built by Dunstons at Thorne 1934), "Southcliffe", "Onesimus", "Hope" (which spent time in Bremerhaven), "Eden". All these are either rigged or will be in the near future. There are a few genuine (most are not) Sheffield keels that come up for sale on the internet from time to time that have been converted to live aboard, "Shirecliffe" is just one of them, the keel "Danum" (second to last keel built at Dunstons) is in France as I believe the keel "Beecliffe" is also. There are many Sheffield size motor barges that are still around; "Dritan", "Sectan", "Richard", "Service", "Enterprise" and Syntan for example, Lincoln keel "Misterton" and Dearne and Dove keel "Pioneer" are other early but now un-rigged sailing barges still around. The list could be long so I'll stop now. Sorry if I missed someone.

Gone was the sight of the powerfully rigged Humber sloops beating to windward through Hull Roads in the short Humber swell to make the Old Harbour before the ebb. Although it is reported that several sloops sailed to Scarborough during WW1 to collect timber from a torpedoed ship, the threat of being sunk by mine or U-boat at the start of WW1 brought an end to the regular coasting trade for the sloop, never to return with the same vigour after the war. Reference as to how many vessels were sunk off Spurn Point and within our Lincolnshire coastal area can be found in David Boswell's book, Loss list of Grimsby vessels (Grimsby Borough, 1969, SBN 900007-00-1. Any cargo vessel leaving or entering the Humber under sail was a prime target for the U-boats. Gone was the sight of the powerfully rigged Humber sloops beating to windward through Hull Roads in the short Humber swell to make the Old Harbour before the ebb. Although it is reported that several sloops sailed to Scarborough during WW1 to collect timber from a torpedoed ship, the threat of being sunk by mine or U-boat at the start of WW1 brought an end to the regular coasting trade for the sloop, never to return with the same vigour after the war. Reference as to how many vessels were sunk off Spurn Point and within our Lincolnshire coastal area can be found in David Boswell's book, Loss list of Grimsby vessels (Grimsby Borough, 1969, SBN 900007-00-1. Any cargo vessel leaving or entering the Humber under sail was a prime target for the U-boats.

In the years between the wars the majority of sloops and keels on the Humber had been de-rigged and fitted with an engine, toward the start of the WW2 this was done using an MOD grant through the Transport Assistance Act. Most were fitted with a wheel house at the same time or soon after. Phyllis however wasn't registered as having an engine until 1943 and a wheel house was fitted in 1962 with her second engine, the HKSPS sloop "Amy Howson" or keel "Comrade" never were fitted with a wheel house.

So came the demise of trade under sail on the Humber that concluded with the de-rigging of the last Humber sloop still sailing, Barraclough's "Sprite" in 1950. Sprite had been built in 1910 for Scott's of Selby at W H. Warrens, yard number 79 at 68ft Loa by 17ft 6" beam with a depth of hold of 7ft 6". Her last captain under sail was Jack Chant of Barton.

P hyllis, presumably as with other Humber sloops of her time designed and built by the Warren family like Nancy, John William, Elma AB and Sprite, had been built to the same relatively fine lines as her 19th century wooden hulled predecessors and dates from the final chapter of the sea going cutter-rigged sloops having been launched in 1907. Phyllis has never had a cutter rig or worked further away from the Humber than Withernsea just north of Spurn Point but she has a Certificate of British Registry, No 58/1907, something required if any vessel was intended to work seaward but is not proof she did. In many cases these ships were used to secure loans and were mortgaged to the banks, they would first have to be British Registered Ships. Eventually "Phyllis" will be making voyages with us along the coast so she has now been cutter-rigged with steeving bowsprit. Her sail plan is based on the sea going sloops of the late 19th century subtly modified to take advantage of her underwater lines and the fact that she doesn't have to work for a living any more without detriment to her authenticity. As no wooden examples of a Humber sloop now exist she is, at present, the only vessel to be able to accurately represent those in hull shape and size and of course more accurately the later iron vessels. She is also able to demonstrate the type of vessel and sailing rig that made such an impact on trade to and from the Humber region through the industrial revolution and toward the end of the 19th century helping to bring about the growth of the ports on the Humber into World-renowned international trade ports and enabled trade from the north and south east of the country to revolve around the Humber. Left. One of the pictures that had been studied to help re-create the rig on "Phyllis". A newly built and rigged wooden carvel constructed sloop most likely from before 1900 is pictured outside Richard Dunstons sail loft at Thorne. The sails are new so none have yet been treated with preservative which coloured them ochre. The ribs of a new sloop or keel under construction are visible behind her bow sprit. The picture appears in the book, Sailing Barges of Maritime England by Tony Ellis ISBN 0 906986 03 6. hyllis, presumably as with other Humber sloops of her time designed and built by the Warren family like Nancy, John William, Elma AB and Sprite, had been built to the same relatively fine lines as her 19th century wooden hulled predecessors and dates from the final chapter of the sea going cutter-rigged sloops having been launched in 1907. Phyllis has never had a cutter rig or worked further away from the Humber than Withernsea just north of Spurn Point but she has a Certificate of British Registry, No 58/1907, something required if any vessel was intended to work seaward but is not proof she did. In many cases these ships were used to secure loans and were mortgaged to the banks, they would first have to be British Registered Ships. Eventually "Phyllis" will be making voyages with us along the coast so she has now been cutter-rigged with steeving bowsprit. Her sail plan is based on the sea going sloops of the late 19th century subtly modified to take advantage of her underwater lines and the fact that she doesn't have to work for a living any more without detriment to her authenticity. As no wooden examples of a Humber sloop now exist she is, at present, the only vessel to be able to accurately represent those in hull shape and size and of course more accurately the later iron vessels. She is also able to demonstrate the type of vessel and sailing rig that made such an impact on trade to and from the Humber region through the industrial revolution and toward the end of the 19th century helping to bring about the growth of the ports on the Humber into World-renowned international trade ports and enabled trade from the north and south east of the country to revolve around the Humber. Left. One of the pictures that had been studied to help re-create the rig on "Phyllis". A newly built and rigged wooden carvel constructed sloop most likely from before 1900 is pictured outside Richard Dunstons sail loft at Thorne. The sails are new so none have yet been treated with preservative which coloured them ochre. The ribs of a new sloop or keel under construction are visible behind her bow sprit. The picture appears in the book, Sailing Barges of Maritime England by Tony Ellis ISBN 0 906986 03 6.

|

|

This site provides a brief history of a the Humber sloop and gives a comparison to more well known types of local vessels. The aim is to bring an understanding of the roll of the Humber sloop to people interested in maritime history or to members of any heritage organisation and to put down in writing some of the background of the Humber sloops that made the River Humber a gateway to the world for the industries of Lincolnshire Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire during the 18th, 19th and 20th century. Not much has been explained in any detail about the sloops of the Humber, the keel has had most of the historic recognition in the past with often just the incorrect comment that the sloop was the same as a keel but with a fore and aft rig. Only after understanding the history of the Humber sloop and its variants can people then begin to appreciate the importance of them in our regions industrial growth and its maritime heritage. Phyllis is not a museum ship or intended to be hired out for trips or functions, she is privately owned by Kath Jones and myself Alan Gardiner. However, we would be pleased to be invited to bring "Phyllis" to maritime and waterways events. Work on Phyllis during her restoration has at times been difficult, the drive to restore her comes from the wider interest we have in the sailing barges of the Humber fuelled by meeting people with similar interest, some of whom were once a part of the industry. Above deck Phyllis has the character of a 1907 working sloop, below she will eventually be our home with all mod cons, with her we will visit festivals and maritime events when and where we can during the summer months. Thanks must go to the HKSPS who have granted me permission to use pictures from their archives and who initiated my interest in Humber sailing barges and to Rodney Clapson who helped to save "Phyllis".

This site provides a brief history of a the Humber sloop and gives a comparison to more well known types of local vessels. The aim is to bring an understanding of the roll of the Humber sloop to people interested in maritime history or to members of any heritage organisation and to put down in writing some of the background of the Humber sloops that made the River Humber a gateway to the world for the industries of Lincolnshire Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire during the 18th, 19th and 20th century. Not much has been explained in any detail about the sloops of the Humber, the keel has had most of the historic recognition in the past with often just the incorrect comment that the sloop was the same as a keel but with a fore and aft rig. Only after understanding the history of the Humber sloop and its variants can people then begin to appreciate the importance of them in our regions industrial growth and its maritime heritage. Phyllis is not a museum ship or intended to be hired out for trips or functions, she is privately owned by Kath Jones and myself Alan Gardiner. However, we would be pleased to be invited to bring "Phyllis" to maritime and waterways events. Work on Phyllis during her restoration has at times been difficult, the drive to restore her comes from the wider interest we have in the sailing barges of the Humber fuelled by meeting people with similar interest, some of whom were once a part of the industry. Above deck Phyllis has the character of a 1907 working sloop, below she will eventually be our home with all mod cons, with her we will visit festivals and maritime events when and where we can during the summer months. Thanks must go to the HKSPS who have granted me permission to use pictures from their archives and who initiated my interest in Humber sailing barges and to Rodney Clapson who helped to save "Phyllis".