|

|

|

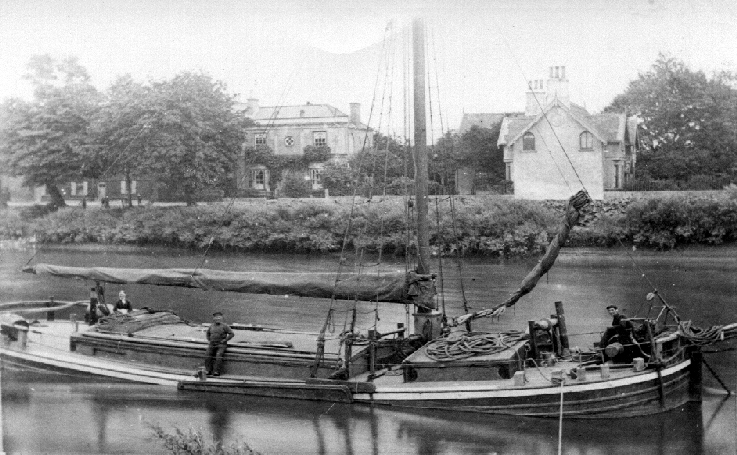

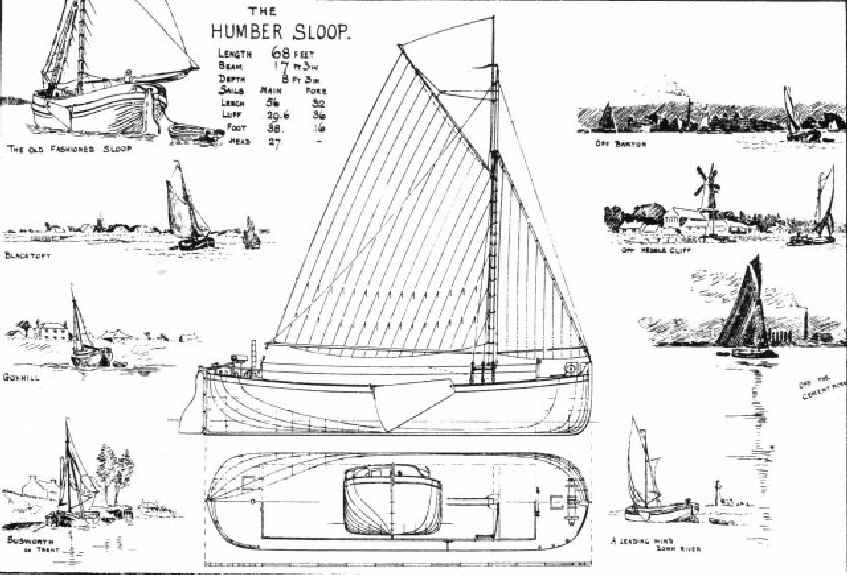

Phyllis 1907. Loa 68ft, Beam16ft.4, Draft 7ft.4, Official Number 124785. Yard Number 60. Sail Number 26148. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Updated: April 2016 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

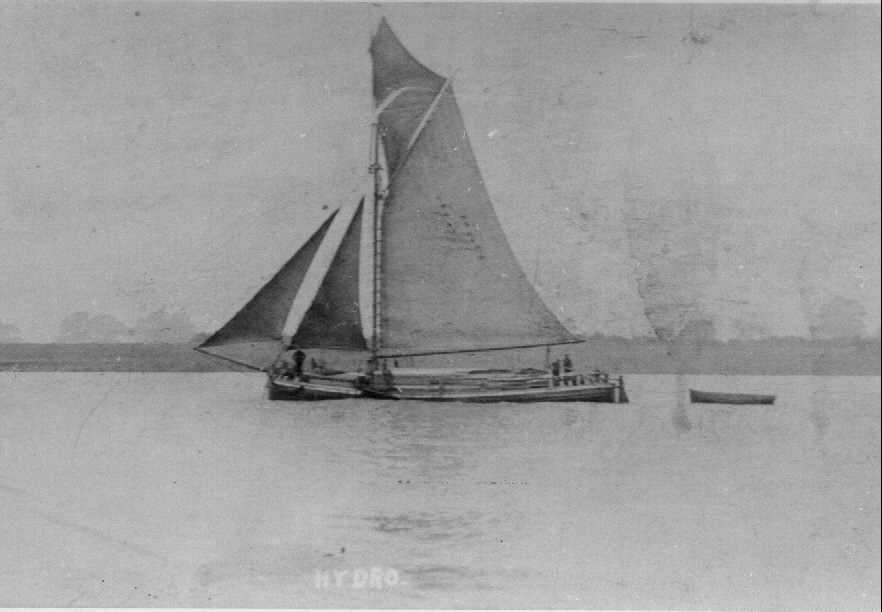

Sailing at South Ferriby |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

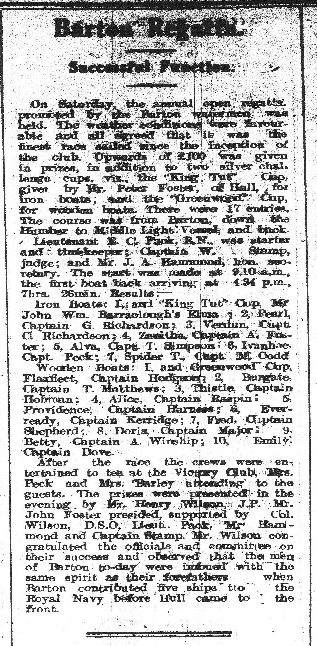

Barton Watermen's Regatta. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sports days and regattas were a very popular event for the local communities who lived on the banks of our rivers. They had been held for a hundred or more years at wharfs and staithes the length of the Humber and its tributaries located at the many prominent towns and villages such as Stainforth, West Stockwith, Owsten Ferry and Gainsborough. South Ferriby also had its day of sport and was able by its location to utilise both the Humber and the River Ancholme, with yacht races and motor boat races on the Humber. South Ferriby was perhaps one of the larger and more popular regattas or sports days on the calendar holding two such events per year. Reports of large crowds of people arriving from Hull on the steamer "Isle of Axholme" was documented in the Hull Times of 9th August 1913. Events like the greasy pole, barrel races and sculling a cog boat over a course with and without blindfold were common to most of the sports days but more unusual (at least today) events were very popular. The ladies log sawing was well attended, as was the duck hunt in which a number of flightless ducks were released to be re-caught by the competitors, whether in the water or not. A washing competition for girls was another featured at the South Ferriby Regatta of 1913. In all the sports days in the area there were only two places where the events involved a barge race. Hull had been hosting a regatta since 1874 and had for its climax of river races the keel race, either up or down river depending on the state of tide. The Hull Regatta and the keel races continued until 1903. The second place was Barton upon Humber, where a regatta was established in 1887, no doubt following a similar format to the one at Hull with various activities on the river involving small sailing boats and games. Again the whole event centred on the barge match, this time with sloops. The race was known as "The Cock of the Humber" and to the winning captain was granted the privilege of flying a copper cockrel atop the mast for that year.The Barton Watermens Regatta continued until the outbreak of war in 1914. After the war years Barton's regatta was resurrected by the Barton branch of the British Legion in 1922 just one year after the Legion was formed on 15th May 1921. The organisers of the Barton Watermans Regatta before WW1 would have been a committee of Barton and district merchantmen, traders and watermen. By 1922 the organisers were perhaps the very merchantmen and traders of the pre war days, but who were now the doctors, prominent businessmen, shipbuilders, JP's, Army and Royal Naval Officers of the town representing the Royal British Legion. The major players in this resurrection in 1922 and those who gave continued support of the Barton regatta where; Mr Henry Wilson JP (President), Lieutenant Colonel H. G. Wilson DSO.JP (Vice President), Mr H. Screeton (Chairman), Mr D.K. Ockleton (Secretary), Captain William Stamp (Judge), Mr Oswold Foster (Judge), Chief Officer E.C. Pack RN, Coastguards (Time keeper), Sir J.D. Berkley Sheffield, Bart, MP., Sir W.A. Gelder, Dr Bradnack, Mr J.C. Stevenson, Mr P.M. Hornsby, Mr B. Barraclough Jnr., Mr James Barraclough JP., Mr W.H. Warren, Messrs Clapson and Sons,Mr W. Harvey JP., Mr O. Wass JP., Major George Canty C.C., Mr W. Dewey, Mr W. McGraw, Mr D.W Massey, Mr J.A Hamond. Enthusiasm for the event was fuelled by the offer of a cup to be provided by Lt Col Wilson named as the "Challenge Cup", and it was reported, "life was infused into the project". The first race held on 5th August 1922 attracted 10 vessels. "The competition was open to all class of river cargo boat, iron or wood". All vessels with a crew of no more than 5 persons to start from anchor with sails furled using only two sails and towing a cog boat for safety; burgees or a pennant of distinguishing colours to be flown for identification by the race judges. The race was to start off Barton Point at 08:00 with the comparative cannon fired at 07:55. The race was reported on thus; " Fortunately, the weather was all that could be desired, and the public by their presence at the Humberside made the event popular. Ten vessels competed but only four of them completed the course. The course was round Burcam Buoy. The following were the successful competitors:1. Eva and Lucy (captain. Arthur Headley) time 3:21 pm. 2. Lucy (captain. John Simpson) time 3:30 pm. 3. Dora (captain. J. Codd) time 4:31 pm. 4. Providence (captain. F. Harness) time 4:40 pm. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Site created May 2009 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

By Kath Jones & Alan Gardiner. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| If anyone has any memories of working for James Barraclough or have a story about working on Phyllis or any of the Barraclough barges we would like to hear from you. If you have any comments or questions on the content of the site or would like to add something to it regarding any of the sloops we would also like to hear from you.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Interesting Links |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Humber Keel & Sloop Preservation Society. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Goole Waterways Museum. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dutch Barge Association. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In The Boat Shed. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The presentation of prizes took place at the Victory Club in the evening, which was filled with seamen and other ex-service men. Mrs Stevenson whose husband on behalf of his wife stated that the occasion was particularly pleasing to her carried out the presentation of the prizes. Mrs Stevenson's late father had been the pioneer of the Regatta". After the success of the 1922 regatta a repeat of the event was assured in future years. Reports of the event varied in detail from year to year and not all the vessels involved were recorded. In 1923 the wooden vessels were given 30 minutes head start on the steel vessels and by 1925 the "Challenge Cup" had been won outright by Capt Frank Hoodless with the sloop "Cranbeck" on winning the competition for the third year in succession. A replacement cup was to be provided by Col Wilson. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Humber Packet Boats. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leicester Trader. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Humber Yawl Club. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brilliant Star | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Capt Harry Hodgson retained the Greenwood Cup in 1929 after winning it for the third time in succession with the sloop "Faxfleet", Mr J.J Greenwood offered another cup to replace it but as we now know it was to be the last race. No official account of the incident concerning "Saxby" and the running down of the cog boat of "Zenitha" in that last race can be found. Capt Arthur Foster on "Zenitha" entered in his diary "Came second" and underlined it several times. No doubt an indication of his frustration. To add insult to injury one of Capt Fosters crew demanded a wage for the day. Needless to say, he didn't get it.  |

| [Home Page] [A Short History] [The Building] [Documents] [Sloop Plans] [The Rescue] [Phyllis at Work] [The Journey Home] [The Restoration.] [Square Rigged Sloops] [Gravel Sloops] [Barton Regatta] [Water Colour Sloop] [Back Under Sail] [The Clippers] [Picture Gallery] |